In Italy, the destructive herbivores can cause up to $22 million of agricultural damage a year.

Rome On a cool night in late September, zoologist Andrea Monaco walks silently through the sandy shrublands of the Presidential Estate of Castelporziano, a protected area just outside of Rome, toward a family of trapped wild boars. Upon seeing him, the eight bristly piglets and their hundred-pound mother try to break through the circular trap’s soft net, only to bounce back to the center. Anchor

Monaco and his colleagues free the sow and one piglet, then enter the 20-feet-wide enclosure to catch the other youngsters for study. Amid the strong smell of wet boar, mud, and feces, one researcher announces with a smile that the baby he was holding had urinated on him.

Several Mediterranean ecosystems thrive in this 23-square-mile estate, such as wetlands, dense pine and oak forests, and sand dunes. Its beauty once attracted Roman emperors and aristocrats who built elaborate villas, which are now reduced to bricks poking out of the loamy soil. Today the area is home to the country's oldest wild boar population—one that Monaco and others are researching in an urgent quest to control the seemingly unstoppable herbivore. (Learn about the battle to control feral pigs in the United States.)

An estimated one million boars, a native species that can weigh up to 300 pounds, now roam the country, destroying crops and causing at least 2,000 car accidents each year, Monaco estimates. And in early 2022, African swine fever was discovered in an Italian boar, raising fears that the wild animals could spread the fatal virus to domestic pigs raised for the meat industry.

The problem is not unique to Italy, either. Due largely to urbanization and forest regrowth, wild boar populations are expanding across Europe, with sightings and close encounters on the rise in many European metropolises, from Berlin to Madrid to Warsaw.

"It is a species that is exceptional from an ecological point of view—super-adaptable and with an enormous reproductive potential,” said Monaco, who has been studying the country's wild boars for more than 20 years at the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) in Rome.

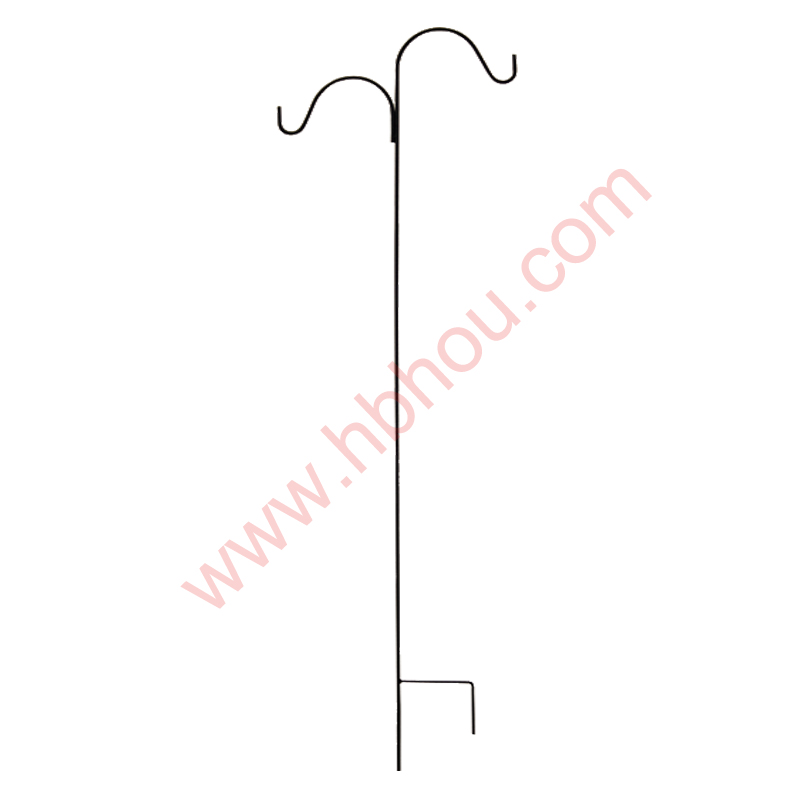

Working with him this evening are 10 other scientists and wildlife experts from around Italy, eager to learn new interventions to stall the boars’ advance. The trap that caught the sow and piglets, for instance, had just arrived from the U.S.: Called a PigBrig, it is lightweight, anchored to the ground like a tent, and can catch up to 60 boars at a time.

Such nets could potentially slow the population’s growth, particularly if many reproductive females are caught, Monaco says. In many cases, the animals are humanely euthanized on the spot, then sold or donated as meat.

Tonight, though, the whole family will survive their encounter, with seven of the piglets outfitted with an ear tag that will allow Monaco to track where they go and how long they live, valuable data for understanding the estate’s boar population.

As the team walks back to their cars in the darkness, Barbara Franzetti, coordinator of the wild boar program in Castelporziano and a biologist at ISPRA, sums up the challenge.

"If we don't change radically the way we manage [wild boars], the population will continue to grow," she says.

Wild boars originated in Southeast Asia and began colonizing the European continent about five million years ago, becoming a favorite food of many civilizations. The animals live in family groups of various sizes, generally consisting of one or more related females and their offspring, as well as other juveniles.

At the beginning of the 20th century, human pressure from deforestation and agriculture drove the species nearly to extinction. Only a few populations remained in Tuscany, southern Italy, and the Alps.

However, after World War II, as Italy’s economy boomed and its population urbanized, forests slowly healed and wildlife returned. Wild boars, opportunistic animals that feed on many foods, including human crops, rebounded—particularly in the absence of the gray wolf, their main predator. (Read about huge feral hogs invading Canada and building “pigloos.”)

What’s more, starting in the late 1950s, Italian hunting groups pushed cities and regional governments to transfer boars from fenced or protected areas such as Castelporziano––and in some cases from Eastern European countries––to stock empty forests. Hunters also privately repopulated their shooting grounds.

This practice continued until 2015, when it was banned. But by then, boars had already become a widespread problem.

In Italy, boars now cause up to $22 million in agricultural damage every year, and though regional governments compensate farmers, often the payment is partial or arrives too late to preserve the crop.

Marco Massera, a farmer in the city of Genova who cultivates vegetables such as zucchini, eggplants, and bell peppers, has been struggling to deter wild boars on his 19-acre farm for the past 15 years. As the pigs forage for roots and grubs, they dig deep underground.

"A boar doesn't eat; it disintegrates. With its muzzle, it pulls up the plants. So once the boar enters, the part it uproots is lost," says Massera, who has received government funds to create fences around his fields.

In the past few years, Massera has also noticed a sharp increase in boars entering his fields close to town, after walking along streets full of people and cars.

Indeed, boars are embracing urban areas thanks to plentiful amounts of unsecured trash and people who are eager to feed them, says Monaco. According to his recent study, wild boars are now a familiar presence in 105 Italian cities, compared with only two a decade ago. To show just how comfortable boars are in the city, he references a viral video taken in Rome in March, which shows two sows calmly nursing their piglets in the middle of a road.

"The moment of breastfeeding in nature is when animals are most delicate and exposed to predation and risks," Monaco says. (Learn how wild boars are making a home in Hong Kong.)

Carme Rosell, an expert in wildlife management and head of the environmental consulting firm Minuartia in Spain, has observed similar boldness in Spanish boars. In her country, the wild boar population has doubled in two decades to about a million animals.

“They have accessed a gigantic pantry: our farm fields and organic urban waste. Nothing has been effective at curbing their population growth—they have no predators; their natural habitat, the forest, is expanding; and winters are less cold,” she says.

“But there is another essential factor: They have lost their fear of human beings.”

In 2005, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to solve the wild boar crisis, Italian government regulators called in hunters. Though Italian boar hunters kill about 295,000 boars annually, the animals reproduce at a faster rate: Every year, their population can grow as much as 150 percent, according to Monaco.

Part of the problem, he says, is that about 30 to 40 percent of Italy’s 500,000 hunters practice caccia in braccata, a communal form of hunting in which a few hunters with dogs herd boars toward other hunters at particular stations, where the animals are then killed. It’s an opportunity to meet friends, be in nature, and have a drink afterward.

Yet this tradition has had a downside: Hunters mostly go after the larger boars, disintegrating the family nucleus and scattering smaller females that will begin their reproductive cycle earlier.

Instead, the government should hire hunters to selectively target reproductive females, which would drastically reduce the population, Monaco says.

But many traditional hunters oppose this idea, both because of its solitary nature and because it would limit boars available for the much-loved braccata.

Massimo Buconi, the president of Federcaccia, Italy's historic hunters' association, is aware of the importance of selective hunting, but says that it would not be enough. He says he believes that only hunters, who can catch dozens of boars at once during a braccata, can solve the problem, and that they should be allowed more autonomy to intervene in protected areas.

Antonino Morabito, an ethologist for Legambiente, a Rome-based environmental nonprofit, notes that hunters and hunting groups often hold political influence in local governments.

"For these people, hunting means a lot, so it affects them when they have to choose who to vote for," Morabito says. "This is the reason why the Italian public administration remains clearly conditioned by this choice."

Other countries have also not seen much benefit from widespread hunting.

In Poland, since 2017, wild boar can be hunted year-round. According to the Polish Hunting Association, in 2021 there were over 4.6 million hunts with 269,000 wild boars shot. Yet the animal is increasingly encroaching into the largest metropolitan areas—it’s estimated there are over a thousand animals in Warsaw, for instance.

Although 400,000 boars are hunted per year in Spain, that country’s population could still double by 2025, according to data from the country’s Institute of Hunting Research.

Uri Shanas, a biologist at Israel’s University of Haifa, recently created a promising experiment that kept boars out of the city of Kiryat Tiv’on.

“Since boars like to wallow in mud to cool off and to get rid of parasites, and to burrow in the mud for food, we set up wading pools for them in natural areas, and it was very successful. They came to the pools, splashed around, played, and had fun, and their excursions into [Kiryat Tiv’on] decreased.”

One of Shanas’ conditions for the duration of the study: No boar culling.

In addition to the ethical and safety considerations, “shooting wild boars does not solve the problem, and in many cases this practice increases reproduction, a phenomenon also found among wolves,” he says.

In Italy, more than 200 boars have been confirmed with African swine fever, and Italians are deeply concerned about the virus’ spread, Monaco says. Each year, Italian farmers raise 8.5 million pigs that sustain a $3 billion pork industry.

After a particularly devastating outbreak in 2018, farmers in China were forced to kill hundreds of millions of pigs to stop the virus’ spread.

This September, Monaco attended the 13th International Symposium of Wild Boars and Other Suids in Barcelona, where, for the first time, a consensus emerged that wild boars need to be contained across the continent.

"People are not worried; they are terrorized by swine fever," says Franzetti, who also attended the symposium. (Here’s how wild boars could spread other diseases to people.)

Researchers shared some wins: The German government, for example, has killed off scores of wild boars using 400 of the American traps Italian researchers tried out in Castelporziano. In Brandenburg, Germany, for instance, “hog damage is down, and hog sightings on the cameras are down,” says Carl Gremse, part of a team working to control African swine fever in the city.

Rosell and her team have collaborated on a guide of deterrent measures for Spanish municipalities, such as making garbage cans and outdoor cat feeders boar-resistant, and populating urban green areas with plants that boars dislike.

In Rome, wildlife officials have installed nets around garbage cans or substituted them with boar-proof models, with some success.

Some animal welfare groups advocate sterilizing females instead of killing them. For instance, Massimo Vitturi, an activist for the Rome-based nonprofit Anti-Vivisection League (LAV) suggests that wildlife officials can inject sows with a drug that renders them infertile.

However, Vitturi admits this approach is limited by the logistics and costs of manually injecting all the female boars one by one. Furthermore, Monaco says that the effects of such treatments vanish after a few years, making sows free to reproduce once again.

Back in Italy, Maria Luisa Zanni has been leading a science-driven approach against boars in Italy’s northern Emilia-Romagna region, where she leads their wildlife planning committee.

She and her team subdivided the area into about 40 square-mile plots, allocating a specific value to each in terms of its impact from wild boars. By identifying where the boars caused more disruption, the team could suggest where local governments should focus stronger eradication efforts and monetary paybacks to farmers.

"With this system, we can reduce the damage a little," says Zanni. However, it’s unknown if this strategy is limiting the boars’ population in her region.

"We are trying hard, but I do not know if we are succeeding," she says. "If there are better solutions outside of Italy, we'll welcome them."

With additional reporting by Eva Van Den Berg in Spain, Slawomir Borkowski in Poland, and Adi Katz in Israel from National Geographic international editions.

Panel Fence Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2022 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved